JEFFREY GIBSON: POWER FULL BECAUSE WE’RE DIFFERENT, HAROLD STEVENSON: LESS REAL THAN MY ROUTINE FANTASY, and NICOLE CHERUBINI, SUSAN JENNINGS AND MICHELLE SEGRE

JEFFREY GIBSON: POWER FULL BECAUSE WE’RE DIFFERENT at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, through September 7, ‘26.

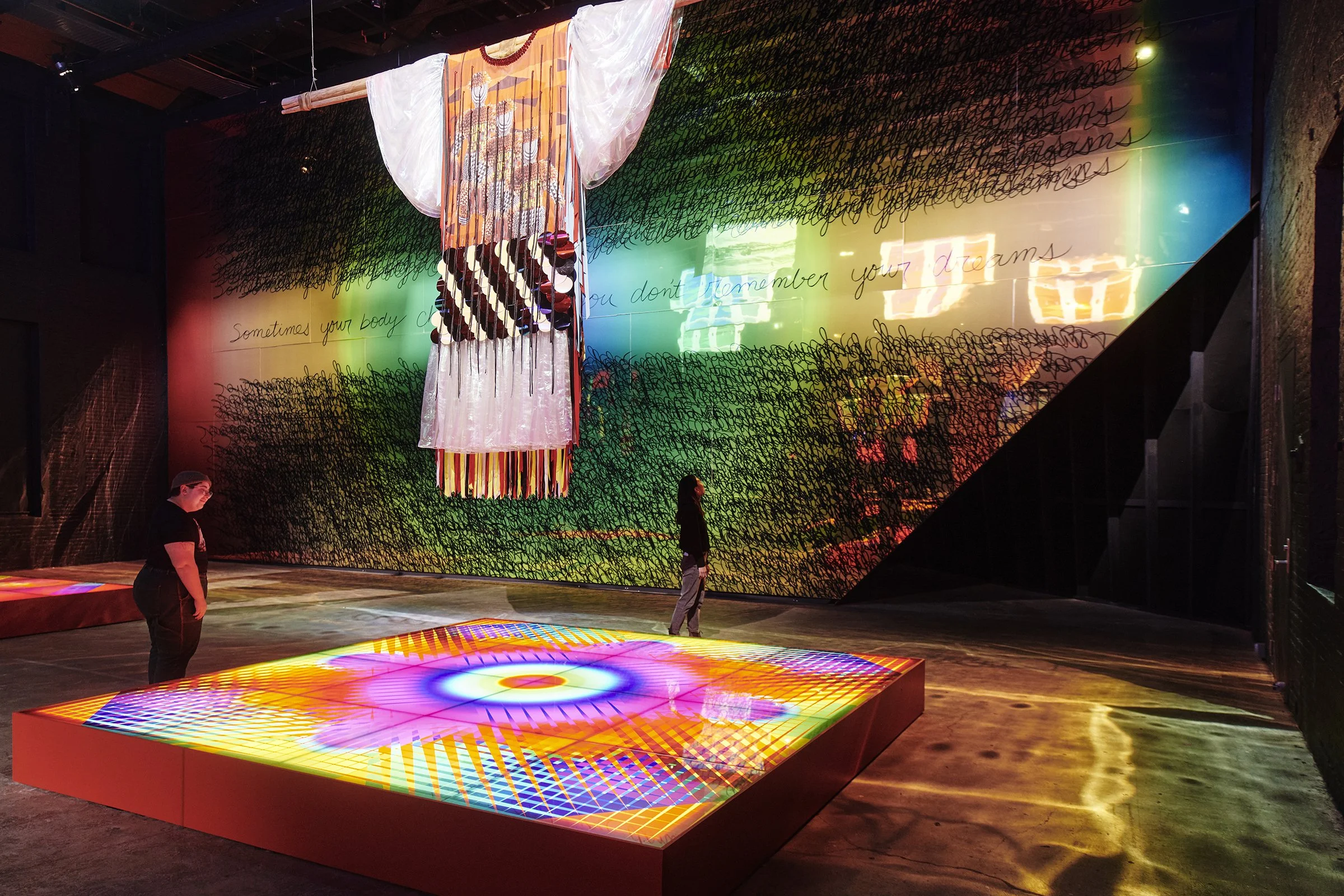

Installation view, Jeffrey Gibson: POWER FULL BECAUSE WE'RE DIFFERENT, 2024-2025, MASS MoCA, North Adams, Mass.; photo Tony Luong courtesy MASS MoCA.

In this dazzling show, Jeffrey Gibson has tapped into the theatrical possibilities of MASS MoCA’s cavernous spaces. POWER FULL BECAUSE WE’RE DIFFERENT features recent installations, videos, and the artist’s unique, outlandish costumes, like wearable sculptures, suspended from the ceiling. Made of a wild array of colorful and glittering fabrics and other materials, these strange kimono-like garments hover above kaleidoscopic platforms made of plexiglass screens emanating colorful, hard-edge geometric designs, which has become a hallmark of Gibson’s art over the years. The show’s title refers to a community full of power, and the presentation is a pulsating, often garish celebration of not only queer identity but of freedom of expression in general, which appears to be increasingly under threat in the nation’s current repressive political climate.

Installation view, Jeffrey Gibson's two-channel video Sometimes your body changes and you don't remember your dreams (2024), filmed by Evan Benally Atwood; photo: Tony Luong courtesy MASS MoCA.

Gibson, of Choctaw and Cheroke descent, represented the U.S. at last year’s Venice Biennale, the first Indigenous artist to represent the country in a solo show at that venerable international showcase. Commissioned by MASS MoCA, the current exhibition seems to be an extension of the Venice show with more high-key sculptures and videos reflecting Gibson’s singular fusion of traditional Native-American motifs and a contemporary avant-garde visual vocabulary. Gibson has refined a kind of psychedelic rhythmic patterning in paintings, as well as in stylized painted texts and beaded details that embellish the sculptures and reliefs, not to mention the full-out techno beats in the videos featuring dancers in elaborate costumes of the artist’s design. One of the highlights in the present exhibition is Sometimes your body changes and you don’t remember your dreams (2024), a mesmerizing, two-channel video installation that is the culminating work in the show. Inspired in part by the late English artist Leigh Bowery (1961-1994), whose gender-fluid personae enhanced by uncanny costumes and makeup, had a significant influence on Gibson’s own performance in the video. Wearing the elaborate costumes on view in the main hall, the artist exudes the feeling of a kabuki dancer’s fierce, defiant intensity within his convulsive yet graceful and sinuous movements. —David Ebony

HAROLD STEVENSON: LESS REAL THAN MY ROUTINE FANTASY, at Art Omi, Ghent, N.Y., through October 26, ‘25.

Harold Stevenson, Les doigts (Fingers), n.d., oil on canvas, four panels; collection Barry Sloane; photo courtesy Art Omi.

Far ahead of his time, Harold Stevenson (1929-2018) was a refined painter and a pre-Stonewall era renegade who unapologetically specialized in the male nude. The Oklahoma-born artist was routinely harassed for his homoerotic paintings and drawings; in 1962 his dealer Iris Clert was jailed for showing them in his gallery, and in 1963, one of his monumental paintings of a male nude was ejected from a show at Guggenheim Museum in New York, where it was to be featured. That same year, he installed a forty-foot-tall portrait of his lover, the famous matador El Cordobés, atop the Eiffel Tower, under the auspices of the French government. After causing serious traffic jams and public outcry, he was forced to take down the painting in less than a week.

During the height of his notoriety in the 1960s and ‘70s, however, he was not without his admirers—Peggy Guggenheim, Andy Warhol, Marisol, Yves Klein, and the actress Glora Swanson, to name a few, were friends and supporters early on. After the 70s, and a slew of bad reviews, Stevenson withdrew from the limelight and eventually returned to Oklahoma. In recent years, however, dealers like Mitchell Algus have called for a reassessment of his work, and last year, a major Harold Stevenson exhibition appeared at Tomasso Calabro Gallery in New York. Harold Stevenson: Less Real than my Routine Fantasy, the current show at Art Omi, curated by Sara O’Keeffe with Guy Weltchek, is a fine overview of Stevenson’s idiosyncratic career, with an emphasis on his finely honed figures, portraits, and carefully calibrated details of body parts, rather than the more scandalous imagery, although there are some sexy paintings here, for sure. There is also a wealth of documentary material on display, which illuminates the life and times of this remarkable and provocative eccentric. —David Ebony

Harold Stevenson, The Mesmerized, 1963; oil and graphite on paper; collection Barry Sloane; photo courtesy Art Omi.

NICOLE CHERUBINI, SUSAN JENNINGS AND MICHELLE SEGRE at Tanja Grunert, Hudson, N.Y., through September 28, ’25.

Nicole Cherubini, Fountain, 2019; mixed mediums with archival print; photo courtesy Tanja Grunert.

The three artists highlighted in this exhibition are united by a shared exploration of novel materials—or combinations of materials—and eccentric spatial relationships. Featuring a dozen major works, the show is handsomely displayed in two rooms of this Tudor-style townhouse named for the Dutch princess and future queen Beatrix, who visited the residence in 1959 to celebrate the 350th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s first fateful journey down the eponymously named river. Following her well-received exhibition of recent works at September Gallery in Kinderhook, N.Y., earlier this year, Nicole Cherubini presents here new and older works, including the arresting photo and ceramic wall relief Fountain (2019) in which two nearly abutting trapezoidal shapes in terracotta and glazed aqua blue ceramic fragments are mounted atop a large black-and white photo of what appears to be a woman wearing an ornate flamenco dancer’s costume. The 3-D elements thwart a clear reading of the photo image, as was the artist’s intention. Cherubini thereby leaves the viewer with a provocative—and exhilarating—conundrum. Fountain raises several important questions: what is the nature of visual language? How do we “read” a photograph? What objects, actions and disruptions in the real world prevent us from accurately perceiving and thoroughly understanding a visual concept or communication? In the present moment of rampant misinformation and politically motivated obscurantism, these issues and questions need to be urgently addressed.

Installation view, Nicole Cherubini, Susane Jennings, Michelle Segre; 2025; photo courtesy Tanja Grunert.

In the same room, Susan Jennings’s Levitating Pink (2025) features a six-foot-high glittering totem of found clear crystal and glass bowls and vases mounted on a black metal pole running through the center of each object. Jennings embellished each intersection of glass with strands of crocheted hot pink yarn in cursive, decorative patterns. The colorful weavings would suggest a humorous yet poignant feminist trope. And the totem, which may indeed have an anthropomorphic countenance, insists on transparency or at least resolute clarity. Michelle Segre’s hanging sculptures, such as Lava Majore (2025) also involve some intricate weaving and suggest cosmic imagery, such as a map the solar system. As author Matt Moment notes in his essay for this show’s catalogue, Segre’s works “radiate celestial whimsy.” They also imply dream catchers and molecular structures. Segre, like all three artists in this show, imagines and invents transcendent, meditative spaces.—David Ebony