UMAN: AFTER ALL THE THINGS . . ., SEEKING COMPLEXITY, and WOODWORKERS OF THE HUDSON VALLEY.

UMAN: AFTER ALL THE THINGS . . . at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT, through May 10, ‘26.

Installation view, Uman: After all the things,. . . 2025, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum; Photo Olympia Shannon; All works courtesy of the artist, Nicola Vassell Gallery, and Hauser & Wirth. ©Uman.

The ground floor galleries of The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum envelop viewers in the colorful, visionary realm of Somalia-born upstate New York-based artist Uman. Most of the large-scale paintings and more intimate works on paper on view appear as abstracted landscapes with outsized leaves, flowers, trees and vegetal shapes flourishing in a multifaceted, ambiguous space that only obliquely references a specific time and place. One of the most striking works on view, amazing grace, glorious morning (2025), for instance, at 9 by 7 feet, features four bands that traverse the canvas from left to right in graceful curves. Each band is topped by a circular form trimmed in red with a magenta interior and a white disk dotted with a pale blue spot at the center. They look like the bulging eyes of a strange creature. The shapes, however, were inspired by an apple tree on Uman’s property in upstate New York, as the artist informed me. The loosely but sumptuously painted background indicates a blue sky, distant horizon, and aerial views of farms and orchards. Hung against a deep-red wall, all the paintings in this room pulsate with a spirited energy.

Uman, amazing grace glorious morning, 2025; Photo David Ebony; all works courtesy of the artist, Nicola Vassell Gallery, and Hauser & Wirth. ©Uman.

In her work, Uman taps into twentieth century modernism’s still-vital and expressive visual language, especially regarding landscape motifs, from Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Picasso, to Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland. For Uman, who also spends a significant amount of time in the south of France, Matisse holds a palpable sway. There are several surprising elements in Uman: After all the things. . . , which was organized by the Aldrich’s chief curator Amy Smith-Stewart. A video room shows Uman’s untitled film (2012-25), a hypnotic loop with images of an icy snow and rainstorm whipping across a field in the middle of the night. The white walls of the spacious rear gallery are covered with irregular patterns of black and grey circular forms that suggests in a wildly imaginative way, another snowy evening. Hung against one wall, a large painting titled and it’s the thing again (2025) features a black curving band at center topped by a white bulbous form. The shape echoes that of a tall black metal lamppost with a white light fixture that has been placed in the center of the room. In comparison with the works in the main gallery, this installation has a decidedly urban feel and functions as a stark and thrilling contrast to the Aldrich’s newly reopened and expanded Sculpture Garden visible through the gallery’s large picture windows. —David Ebony

SEEKING COMPLEXITY at Bill Arning Exhibitions, Kinderhook, NY, through November 23, ‘25.

Deborah Bright, Sir Lady, 2025; Photo courtesy Bill Arning Exhibitions.

A useful curatorial tool, the notion of complexity neatly contrasts with minimalism in a way that encompasses a broad range of artworks, with diverse themes, styles and mediums. This exhibition features works by David Becker, Deborah Bright, Jane Fine, Bo Joseph, Brian Kenny, AJ Liberto, Andy Ness and Harrison Tenzer. While the wide-ranging images and mediums here might seem disparate at first, the unifying thread for this exhibition is Bill Arning’s consistently unwavering eye for high quality, conceptual strength, art-historical depth, and a certain level of artistic sincerity and veracity that is difficult to define and may be completely intuitive. Deborah Bright’s outstanding painting, Sir Lady (2025), for instance, explores gender fluidity by means of a visual language that corresponds knowingly to that of the Chicago Imagists like Ed Paschke and Jim Nutt, but retains a sense of a unique, individualistic expression.

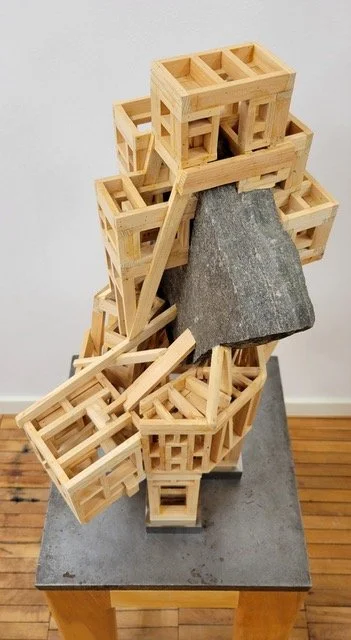

AJ Liberto, Crisscross Applesauce All was Lost, 2019-2023. Photo courtesy Bill Arning Exhibitions.

Similarly, the quasi-Cubist drawings of David Becker, and the Art-brut infections of Bo Joseph’s dense and intense figural compositions contribute to his wholly idiosyncratic vision. AJ Liberto’s intricate and labor-intensive constructions made of wood, stone and found materials, mine but do not mimic modernist precepts by artists such as Sol LeWitt or Michael Heizer. Instead, Liberto creates credible architectonic structures that are full of wit, illusion and grandeur, albeit in an intimate, egalitarian and utopian space. Seeking Complexity seems like an appropriate swan song exhibition as the last of Bill Arning Exhibitions at this Kinderhook gallery, which itself offered the art community an intimate, egalitarian and utopian space for visual thinking. — David Ebony

WOODWORKERS OF THE HUDSON VALLEY at Studio Tashtego, Cold Spring, N.Y., through Dec. 7, ‘25.

Christopher Kurtz, Waveform Bench, n.d., Photo courtesy Studio Tashtego.

Woodworking has had a long and noble tradition in the Hudson Valley. This exhibition brings together fifteen contemporary artists working in a variety of styles and techniques. Furniture and utilitarian objects are in the mix, as well as purely sculptural objects that have no function other than visual and intellectual stimulation. In his elegant work, Waveform Bench, Christopher Kurtz seems to straddle both worlds. The cornflower blue painted wood piece more than six feet long is a refined undulating form that represents an ocean wave yet serves very well as a welcome bench for the weary—as I can attest having had the pleasure of sitting on it. It could also be equally at home in the midst of a sculpture show of works by Jean Arp, Brancusi, or Saint Clair Cemin.

Nadia Yaron, Pink Vessel on a Broken White Column, n.d; Photo courtesy Studio Tashtego. .

Among other outstanding works, Nadia Yaron’s rough-hewn sculptures such as Flower and Cloud and Pink Vessel on a Broken White Column, with its lively multi-color stains, allude to tribal art as well as to the contemporary craft tradition to which they also comfortably belong. Here and throughout the exhibition the confluences between fine art and craft blend, blur and complement each other. —David Ebony